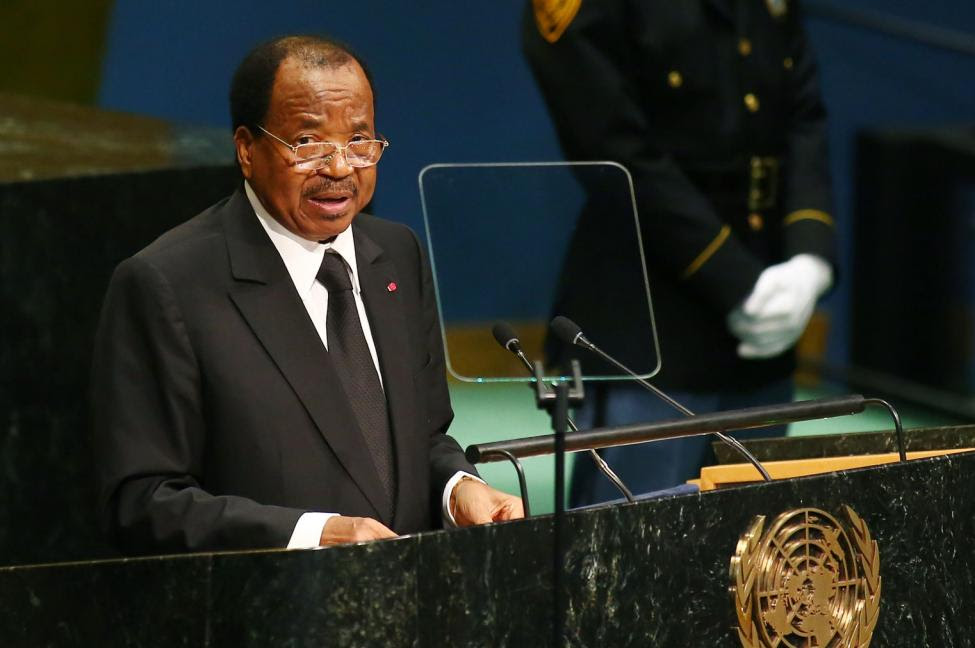

Oct. 26 (UPI) — The re-election this week of Cameroon’s President Paul Biya — in power since 1982 — could be bad news, not just for Cameroon and the region, but for the United States.

Cameroon for a long time was regarded as a paragon of stability in a part of the world too often marked by insecurity, civil wars and coups. During the Cold War, the country remained close to France, which served French political and economic interests while also suiting the United States, which appreciated French dominance in the region as a barrier to Soviet influence, not to mention Cameroon’s status as a modest but stable oil producer.

More recently, in 2013, Cameroon emerged as a valuable counterterrorism partner when the Boko Haram insurgency spilled over from neighboring Nigeria. Cameroon’s military joined the fight alongside regional militaries and with the backing of France and the United States, which boosted security assistance to the country, according to USAID data (the level of aid has since dropped), although as many as 300 U.S. soldiers remain deployed to the country to support and train the Cameroonian military. Cameroon also benefits from French security assistance (in 2013, Cameroon played a key role in France’s military intervention in the Central African Republic as a logistical hub and port of entry). Bolstered by outside help, the Cameroonian security forces have proven remarkably effective.

The problem is that under Biya, the Cameroonian government is rapidly becoming more authoritarian and bloody-minded, making insecurity worse, rather than better. The country’s days as a reliable partner seem numbered.

In the fight against Boko Haram, the Cameroonian military has racked up a deplorable record of human rights abuses committed against civilians in the name of counterterrorism, including abuses committed by the American-trained Rapid Intervention Brigade. This summer, videos emerged of Cameroonian forces killing civilians, including particularly shocking footage of an execution of women and children. One of the women was shot with a baby strapped to her back, which was also killed.

Cameroon’s harsh tactics might be working, at least in the short term: Violence committed by Boko Haram has declined, according to data collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project. History, however, suggests that Cameroonian forces are only sowing the seeds of future conflict. The bloodshed, moreover, increasingly is overshadowed by a much more dangerous conflict that is entirely of the Cameroonian government’s making: A violent insurgency in the country’s English-speaking regions, known as Ambazonia, a vestige of British rule over a portion of the country after Britain and France took the country from Germany at the end of World War I.

The conflict has been “decades in the making,” ever since 1972 (before Biya), when Cameroon’s government abandoned federalism and tried to integrate the once British-governed regions into a centralized state without taking steps to protect the rights of anglophones, heed their interests or ensure their enjoyment of a proportionate share of benefits and opportunities. Thanks largely to heavy-handed repression under Biya, people who might once have protested peacefully have now taken up arms, to which the government has responded with mounting violence. The entire crisis, it must be stressed, was entirely avoidable, as at any point since 1972 the country’s leaders might have found ways to accommodate better their anglophone communities.

Under Biya, Cameroon is on track to become weaker and less stable, and therefore less useful as a partner, even if one were to set aside the question of the propriety of working closely with an increasingly abusive regime. Indeed, even French President Emmanuel Macron reportedly has been slow to congratulate Biya for his election victory. Rather than being part of the solution to the region’s terrorism problem, Biya may be becoming part of the problem.

By Michael Shurkin

Michael Shurkin is a senior political scientist at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corp.