[spacer style="1"]

Sassou rules like an emperor while Congolese die from extreme poverty

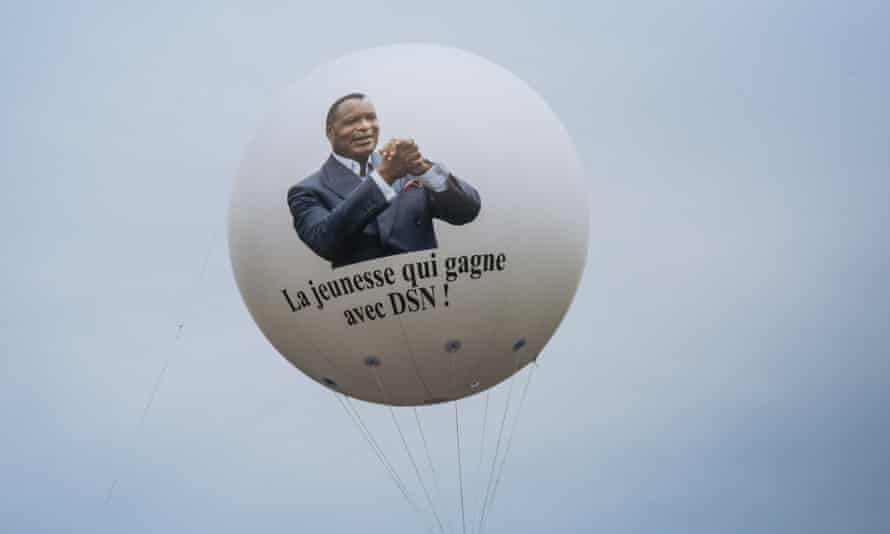

The result of last month’s presidential election in Congo-Brazzaville brought no surprises. After 36 years in power, Denis Sassou Nguesso, 77, clinched 88% of the vote with a turnout of more than 67%. Accusations of vote irregularities, including ballot box stuffing, were widespread. His closest rival, who had urged for a “vote for change” died of Covid on the day of the vote.

Television showed a triumphant Sassou at home with his smiling henchmen, as the interior minister, Raymond Zéphirin Mboulou – instead of the head of the electoral commission – announced the win. The question now is whether or not the African Union, the US, the EU, the UK and former colonial power France will simply turn a blind eye to another disputed election result while Congolese are dying from extreme poverty?

Sassou made the briefest of victory speeches: “By this vote, the people in their majority responded and said that we had the capacity to bounce back, to recover our economy, and to move towards development.”

I wonder how can this country bounce back and recover when Sassou is ruling it like an emperor?

An election brings legitimacy, even if it is as blatantly see-through an exercise as the emperor wearing his new clothes

First elected in 1979, Sassou has been in power for 36 of the 61 years this oil-rich central African country has been independent. This victory extends his rule to 2026. Sassou has known six French presidents, from Valéry Giscard d’Estaing to Emmanuel Macron. By the end of 2026, he will have been in power for longer than Joseph Stalin and Central African Republic’s dictator Jean-Bédel Bokassa combined.

From its Soviet Union days, Congo-Brazzaville, a country of 5.5 million souls with a median age of 17, has never been a democracy, or a republic in liberal terms. Sassou rules it with an iron fist. His 2016 electoral “win” sparked violence across the country.

During the 2021 campaign, Sassou ordered internet services to be shut down for almost a week, including on election day.

The democracy watchdog Freedom House, which scores countries on their political and civic freedoms, lists Sassou’s Congo as “not free”. The UN’s Human Development Index positions the country at 149 out of 189, two points above war-torn Syria. Yet, Congo is Africa’s sixth-biggest oil producer, earning huge revenues. However, amid Sassou’s kleptocracy, the country remains paradoxically poor, with nearly half the population living below the poverty line.

The economy, too, is stagnant. Civil servants go months without wages and pensions. Hospitals go months without basic medicine. Transparency International’s corruption perceptions index ranks Congo-Brazzaville among the world’s top 20 most corrupt countries.

Sassou’s mismanagement is a family affair. His daughter Julienne Sassou Nguesso and her husband, Guy Johnson, have been charged with corruption and money laundering in France. Global Witness alleged in April 2019 that his other daughter Claudia Sassou Nguesso, who is an MP and the president’s head of communications, received almost $20m (£15m) of apparently stolen state funds and used it to buy a luxury flat in Trump Tower, New York, allegations she denied.

His son, Denis Christel Sassou Nguesso, also an elected member of the Congolese parliament, is being groomed to succeed his father. He also allegedly took more than $50m from the Congolese treasury funds for his personal gain, according to a Global Witness investigation.

Unsurprisingly, many of Sassou’s most vocal opponents, including his former challenger Jean-Marie Michel Mokoko and his former minister André Okombi Salissa, have either been jailed, exiled or are dead. This has left no credible alternative to his son when Sassou exits politics.

Not long before the March 2021 election, human rights defender Alexandre Ibacka Dzabana was arbitrarily arrested by Sassou’s intelligence officers. He is still detained in Brazzaville where he has been denied access to his lawyer and family. Yet there is barely any indignation from outside the country.

In 2019, Sassou announced the discovery of new oil deposits which would increase the republic’s daily production from 350,000 barrels a day to 980,000, tripling Congo’s revenues from the oil and natural gas sector. Perhaps this is why power has not changed hands by the ballot box, and serious reforms have not been enacted, while the international community sees nothing, hears nothing and does nothing.

Why, then, you may wonder, does Sassou bother with the charade of a multi-candidate election at all? Why hasn’t he yet declared Congo a personal fiefdom, and crowned himself an emperor like Bokassa did in CAR, something his peers, including the president of Guinea, Alpha Condé, and Ivory Coast’s Alassane Ouattara, call him publicly?

Because, as other kleptocrats have discovered, an election brings legitimacy, even if it is as blatantly see-through an exercise as the emperor wearing his new clothes. Sassou – the warlord who overthrew democratically elected Pascal Lissouba to reinstate himself as leader, igniting a civil war that left thousands dead and remains an open wound in the country – wants unlimited power, perhaps for the duration of his life. But Sassou also wants international approbation. Surely an opportunity for the international community to capitalise on?