It is an odd thing to live somewhere gripped by deadly conflict. One may imagine that the pain and challenges of one’s day-to-day life would also weigh heavily on the outside world. But that is not usually the case. In many crises, the rest of the world does not know – or does not want to know.

If you live in the English-speaking regions of Cameroon, for instance, you might wonder why the atrocities that have been happening on your doorstep for the past three years are rarely mentioned in the global media or at United Nations meetings. There are no consequences for Cameroon’s government soldiers and radicalized separatist militias’ actions, which have looted and burned homes and schools, while killing and mutilating civilians. Some 656,000 English-speaking Cameroonians have abandoned their besieged villages. And on Feb. 14, state forces allegedly perpetrated a massacre in the remote locality of Ngarbuh, killing at least 20 people – including many children. Only then did the crisis manage to make the news.

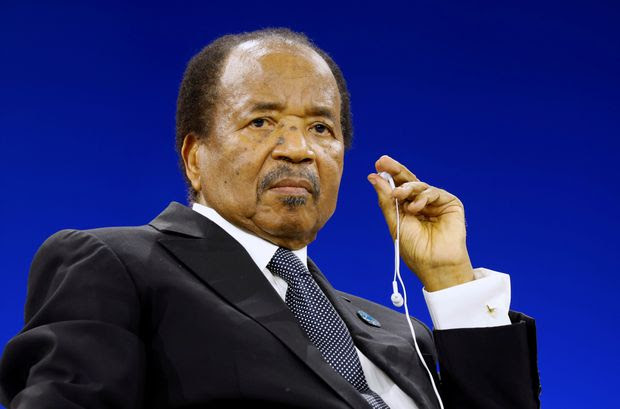

The Cameroonian government, led by Paul Biya, who has served as President since 1982, has signed numerous UN conventions promising to uphold human rights; yet, it repeatedly violates them without repercussions. Cameroonians are left to feel that impunity will triumph so long as the UN lacks the power or will to enforce its high-minded conventions.

To cite Juan Mendez – an Argentine lawyer, torture survivor and former UN rapporteur and adviser on the prevention of genocide – one must be a grain of sand in the eyes of the world’s diplomats and decision-makers. That is how suffering gets attention: with persistent irritation of international bodies such as the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC).

With a firmly lodged grain of sand, would the UN be able to end Cameroon’s impunity using international law? Yes, if the 2005 Responsibility to Protect doctrine (R2P) is invoked.

The UNHRC meets in Geneva at the end of the month, and it is doubtful that the worsening security situation in Cameroon will be on its agenda. However, the council surely has enough information on what is happening in Cameroon to consider R2P. In 2016, peaceful demonstrations by English speakers were met with disproportionate force. In 2017, the UNHRC received a report detailing the UN’s concerns about the lack of freedom of expression or assembly in Cameroon, the arbitrary detention and torture of journalists and opposition politicians, the lack of independence among the judiciary and the people running elections, and discrimination against the English-speaking minority.

In 2018 and 2019, the conflict in Cameroon spiralled out of control. International human-rights groups have reported that the francophone-dominated government allows the military to use lethal force against armed separatists and civilians alike. As a result, some separatist militias have become increasingly extremist and violent, and social-media platform WhatsApp is now saturated with videos of torture and death perpetrated by both sides. Moderate anglophone activists and innocent civilians are caught in the middle, and cruel violence and horrific acts increased in the period around legislative and municipal elections held on Feb. 9, with no end in sight – all this, before last week’s Valentine’s Day massacre.

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights visited Cameroon in May, 2019, and urged the government to hold members of its security forces committing abuses to account. This diplomatic language was echoed by the Council of the European Union. However, it is not just a few rogue elements committing human-rights violations: Cracking down on the English-speaking regions is actually government policy.

In August, 2019, a group that included Lawyers’ Rights Watch Canada, the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights, and the Centre for Human Rights and Democracy in Africa made a submission to the UNHRC about the unfolding human rights catastrophe, calling for the council to help end the violence and investigate grave human-rights violations, including crimes against humanity – for which the UN could invoke R2P.

Adopted in the wake of the 1994 Rwandan genocide, R2P has three pillars. First, it stipulates that countries have a duty to protect their own citizens from the four mass-atrocity crimes: genocide, crimes against humanity, ethnic cleansing and war crimes. Second, the international community must encourage and assist states if they are unable to fulfill their duty to protect their citizens. Finally, if a state fails to protect its population, the international community must be prepared to take appropriate collective action in a timely and decisive manner and in accordance with the UN Charter. This action can consist of diplomatic measures, such as mediation or sanctions, or sending in peacekeepers.

The most recent analysis from the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect considers Cameroon to be “in imminent risk of reaching a critical threshold” where mass atrocities may occur “in the immediate future.” It cites the most up-to-date UN Office for the Co-ordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) report, which says 5,500 English-speaking Cameroonians fled their homes in just one week, between Dec. 9 and Dec. 15, 2019, because of military operations in northwest Cameroon; it also advocates for access to investigate human-rights violations and abuses and calls for a suspension of military aid to the country.

But despite the report’s conclusion that the government must hold inclusive talks with the English-speaking community, mediated by a neutral player – the Swiss Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue has offered to serve in that role – the Cameroonian government has refused to take part.

History shows that if the international community lets a government know that the world is paying attention, it can make a difference. General Roméo Dallaire, the UN commander in Rwanda, said that if the UN had sent a brigade of peacekeepers, its mere presence could have prevented the murder of hundreds of thousands of Rwandans in 1994. Instead, the UN pulled out its peacekeepers, signalling to the Hutu extremist government that it could do whatever it wished.

This month, the UN Human Rights Council has an opportunity to signal its seriousness to Mr. Biya. Cameroon’s crisis should no longer be a grain of sand, but rather a shard of glass in the international community’s collective eye. R2P can save lives and start the path to peace. The reprehensible killings in Ngarbuh demand action.

Felix Agbor Nkongho and Rebecca Tinsley

Contributed to The Globe and Mail

Felix Agbor Nkongho is a Cameroonian human-rights lawyer and president of the Centre for Human Rights and Democracy in Africa.

Rebecca Tinsley is a Canadian journalist and the author of When the Stars Fall to Earth.