CAMEROON ANGLOPHONE CRISIS

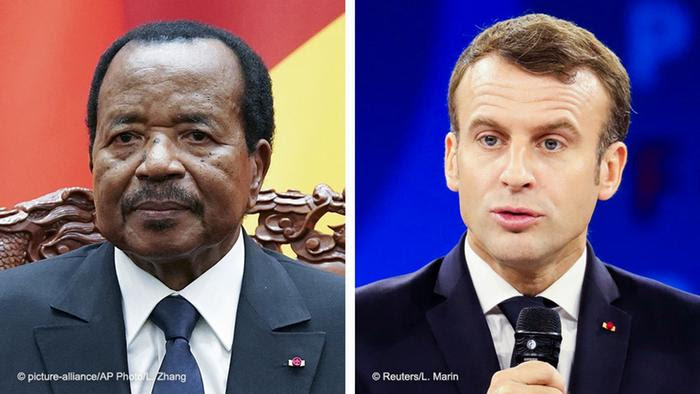

Fifty human rights advocates, scholars and writers have penned an open letter to French President Emmanuel Macron urging France to “up its engagement in resolving Cameroon’s Anglophone crisis” amid ongoing reports of “dehumanizing violence.”

For the past two years, Cameroon’s predominately English-speaking Northwest and Southwest regions have been rocked by unrest after separatists declared the independence of Ambazonia. Up to 3,000 people have been killed in the violence between the separatists and government forces, and more than half a million have fled their homes since the uprising began.

The letter, which was first published in French on Jeune Afrique news site, was released on Tuesday to coincide with the launch of the second Paris Peace Forum in which 27 heads of state — including Cameroon’s longtime President Paul Biya — met with leaders of businesses and NGOs to discuss solutions to global challenges, with a focus on finding “innovative and lasting solutions.”

‘A disturbing and disappointing silence’

Since the beginning of the Anglophone crisis in 2017, the international community has been reluctant to engage in and mediate the conflict.

Rebecca Tinsley, the founder of human rights organization Waging Peace and one of the signatories of the open letter, says the slow response ultimately comes down to geopolitics and the global fight against the extremist group, Boko Haram.

“Basically, the Government of Cameroon is using its own soldiers to fight the war on terror on behalf of the Global North,” she said.

“In the northern part of Cameroon there are people from Boko Haram, thousands of them, causing chaos. It’s a case of the Cameroonian armed forces being a militia for hire. So [Cameroon] has sort of inoculated itself against criticism.”

France maintains strong business and military links with Cameroon — a factor, says Tinsley, that explains France’s limited involvement in the crisis.

“At the end of the colonial period, France never really left its former colonies,” she says. “[Cameroon] has oil, minerals and timber, and the French are very involved in the military and economic future of Cameroon. There is a disturbing and disappointing silence from a country that should be putting pressure on President Biya over his human rights record.”

‘Rwanda in slow motion’

The Anglophone crisis has been described by some analysts as “Rwanda in slow motion” – a reference to the genocide that occurred in Rwanda in 1994 when 800,000 people, most of them from the Tutsi minority group, were slaughtered by Hutu extremists in the space of a few months.

“This is urgent: The dehumanizing violence in Cameroon must not reach the scale of what happened in Rwanda in 1994,” the open letter reads. “While armed non-state groups and bandits use machetes to maim, torture and behead, government forces are committing crimes against humanity such as extrajudicial executions and burning of villages.”

Amid the unrest, separatists have also enforced lockdowns in cities and towns, forcing many schools to remain closed for up to four academic years in a row.

Read more: Cameroon: Kids bear the brunt as armed conflict continues

Peace within reach?

Under international pressure, Biya held national peace talks in October, dubbed a ‘Major National Dialogue.’ Although key secessionist figures boycotted the five days of talks, those that attended made a series of recommendations to try to restore peace.

One of the recommendations was giving the Southwest and Northwest regions a “special status”.

Speaking at the Paris Peace Forum on Tuesday, Biya confirmed his government’s commitment to this recommendation.

“We trying to put in place a special status which recognizes the specificity of the Anglophone region while respecting the territorial integrity of the country,” he said.

However, it is still not clear what this special status might look like and when it would be implemented.

.

Human rights advocate Rebecca Tinsley says a long-lasting solution to the Anglophone crisis will ultimately require the involvement of outside players, with France and the Vatican likely to have the most influence in peace talks.

“The [Cameroonian-led] negotiations never really got to the heart of why there is this terrible conflict…it had no credibility whatsoever,” she told DW. “The only forces that will have any real impact of Biya is the Vatican, because this is a religious country and the French government.

“They are both in a position to push Biya to participate in talks which had been proposed in Switzerland,” she said, referring to an offer by Swiss authorities in June to mediate between Anglophone rebels and the Cameroonian government.

Tinsley is optimistic that Macron will heed the concerned calls of observers.

“Macron understands that France needs to move away from its traditional role in French-speaking Africa…He will want to find a more positive role for France in the region in the future.”

Read more: Cameroon is still a far cry from peace

Parliamentary elections set for February

In a sign that President Biya may be taking further steps to resolve the crisis, the government announced it would hold parliamentary and local elections on February 9, 2020.

These elections should have been held in 2018 in parallel with the presidential election (which was won by Biya), but they were postponed twice after the president said holding all three votes in the same period would be “difficult” due to “overlapping electoral operations”.

Cameroonian activist and politician Kah Walla told DW she is skeptical that elections will bring change.

“We have this cultural problem in the electoral system which has consistently produced bad elections for Cameroon,” Wall said. “We are electing parliamentarians who have no power…so elections are completely useless.”

“We need to reconcile the country. The majority of the regions in the country are [experiencing violence]. We need to discuss a new form of the state and truly decentralize it. Elections are the last step, not the first.”